We acknowledge that the UBC Vancouver campus is situated on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam).

Health Services and Policy

The Division of Health Services and Policy encompasses a range of disciplines and fields including health services research, health policy, health economics, health systems and health ethics. Almost all areas of health care fall under scope and in many cases an applied lens contributes to collaboration with clinicians, health care managers and policy makers. The Division welcomes inquiry about the full range of public policies as they relate to social determinants of health, as encapsulated in the “Health in All Policies”.

Activities within the Division address the organization, regulation, accessibility and utilization of health care resources, and the resulting costs and effects. Topics of interest include large data administration, health and pharmaceutical policy, health reform, organizational change, health care financing, cost-effectiveness, health technologies, program evaluation, priority setting, quality and outcomes of health care, health information, social determinants, health disparities and knowledge translation.

Faculty within the Division contribute to teaching in all of the graduate programs within the School and are actively engaged with graduate students in both supervisory and advisory capacities. Prospective students are encouraged to read the faculty bios to get a sense of individual research interests. The Division is also home to the Health Economics concentration within the MSc program.

A number of research centres also are associated with the Division, including the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research (CHSPR), the Centre for Advancing Health Outcomes, the Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Evaluation (C2E2), the Centre for Applied Ethics (CAE), the Collaboration for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE), the Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP), and the National Core for Neuroethics.

Links

Global and Indigenous Health Theme

- UBC Global Health Hub

- Global Health Research Program

- Center for Excellence in Indigenous Health

- UBC Learning Circle

Maternal-Child Health Theme

Social and Life Course Determinants of Health Theme

- Youth Sexual Health Team www.youthsexualhealth.ubc.ca

- Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) earlylearning.ubc.ca

- Centre for Health Promotion Research blogs.ubc.ca/frankish

- BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS www.cfenet.ubc.ca

- Child and Family Research Institute www.cfri.ca

- Generation Squeeze gensqueeze.ca

- Partnership for Work, Health and Safety pwhs.ubc.ca

- CIFAR Successful Societies Research Program www.cifar.ca/successful-societies

- Population Data BC www.popdata.bc.ca

Interview Series (Dr. Jude Kornelsen)

A Conversation with Dr. Jude Kornelsen

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Ron: You’ve been working on rural health issues from both research and practice perspectives for many years. How are you currently engaged? What do you think are the major issues facing rural/remote BC at this point?

Jude: I’ve been community-focused, i.e., engaged in community-based and community-directed research from pretty much the start of my career and it comes from having the experience of living in a rural community and actually experiencing challenges myself and for my family in accessing health services. In the past, a lot of my work was focused on evidence-based system interventions for addressing some of the access issues faced by rural communities. So, I’ve done a lot of work from a system perspective on looking for example on “population health outcomes” based on distance to services, the local model of care, and evaluating the efficacy of local models. Increasingly, however, it’s become really clear to me that the most effective pathway forward is to nest rigorous evidence that we are collecting alongside community identified priorities and solutions to stabilize local health care. So, I believe that combining these two together creates a very compelling narrative and provides a lot of ground truth for what we’re doing. It’s not at all detached from the realities on the ground. In terms of the major issues, some of them are absolutely no different than what we’re seeing across the healthcare system in general. Lack of access to primary care providers, extended wait time for specialist visits, etc. But, we also know that there are unique challenges in rural settings, and these really stem from some of the specific characteristics of rural, namely isolation and low population density, which means there’s no specialist safety net for complex or emerging care. Some of the issues we’re contending with right now include the constriction of what’s offered locally. So, we see this most acutely with lack of access to maternity care and also emergency department coverage. Quite frankly, we just have to pick up a newspaper or listen to CBC to hear the pronouncements of constriction of services across rural communities or diversion of services. In fact, in our own community in Salt Spring, last weekend the emergency room was on diversion. This leads to an increased need for patient transport which is challenging as well when we’re on diversion. It’s easy to say ok, we’ll just move them out of the community. But then, how do we move them out of the community when we’re constrained with availability of assets? When an asset like an ambulance leaves the community, it means there’s no local 911 response in many cases depending on the size of the community or at least there’s reduced access to 911 coverage. We know that in rural communities, it’s incredibly difficult to maintain paramedics due to low volume. They’ve done some really well appreciated adjustments to the incentives for paramedics, but we still struggle with how to retain people when there’s not a lot of actual call. It’s very different than the paramedics in Vancouver who are working pretty much full shift, going from call to call. There are also challenges beyond transport. Access to “specialist care” in rural communities, the ones that don’t have a population size for focused specialist practice, means that when specialist care is needed, (and of course we know specialist care will be needed across the population), residents have to leave their community and this might be for a single appointment or might be a series of appointments or course of care such as in the case of cancer treatment. These are the kind of issues that we grapple with trying to maintain an appropriate level of service based on population need for small communities and then, efficiently and effectively getting people out and back when there’s the need for a higher level of care. I’m emphasizing the issue of getting the patients back to the communities because, again, all we have to do is read the news to hear the horror stories of people who are backed out of their community and then released from a regional referral centre with nothing. And often, if it is an emergency situation, you don’t even have your wallet. So, we need to be very mindful about repatriating rural community members back to their community. These are some of the issues that are challenging with rural health right now.

Ron: There are many issues that have been appropriately described as “systems issues”; however, in spite of the rhetoric, are we getting there in terms of a systems approach? Does this approach need to be reframed in some way, e.g., along the lines of current thinking around a ‘learning health system’?

Jude: We are always at risk of sliding into rhetoric, especially with key phrases and this is the case with many key phrases in health system planning. “Learning health system” is one of them, but so is “care closer to home”. Care closer to home is also one of the biggest issues. There are concerns like “what does care close to home mean”? and “where are the accountabilities for ensuring that?” But, let us think for a minute about what a learning health system is and I see it as a system that’s intentionally designed to continuously learn and improve on the basis of data and experience. Then, we have to think about how well the enablers are working right now. In my research experience, there are two issues: timely access to current data; and patient and community engagement. I think we have some challenges accessing administrative data in British Columbia in a timely way for sure and we need to recognize that due to the quickly changing nature of the health care environment. These delays make it very difficult to create feedback loops and to modify the way we’re delivering care in a timely way. Challenges around access to data are about the kind of data we are accessing and, for sure, health outcomes. Administrative data is crucial, but alongside the administrative data we need to be able to access individual patient experience data and community-level data. To understand these data, we need to engage with communities in a longitudinal, meaningful way and not just try to do some kind of focus groups. We do need to be really understanding of their history and context and work alongside, being in partnership with those who live in the communities. This takes time and resources, but it’s really the only way to create robust evidence for health system planning. Yet, are we doing this? I don’t think so. Do we have the potential to do it? Absolutely. So, this is an instance where I would choose to be more optimistic than pessimistic. We’ve got the mandate. We’ve got the mantra. Let’s take it up and let’s truly actualize what a learning health system is and change the system constraints right now for those continuous feedback loops to actually be meaningful and actually change practice. We’re not there yet but I’m hopeful!

Ron: As the saying goes, ‘when you’ve seen one rural community, you’ve seen one rural community.’ This, of course, is very true; yet, somehow, policies, referral patterns, regulations, etc. do not conform to this maxim. How do we address the inherent heterogeneity of rural/remote communities and reconcile with health services planning at the systems level?

Jude: I think this conundrum really prevents people from diving in, in a meaningful way. It’s daunting. Yes, there’s absolutely heterogeneity across rural communities within BC and elsewhere and even within individual health authorities, quite frankly. But, longitudinal engagement allows us to understand these differences well at the same time I believe. I respect the fact that there will be some kind of mid-range theories and by that, I mean those learnings that sit between the broad, comprehensive overarching theories. That reduces everything to commonalities. In essence, mid-range theories are on that kind of micro-variation by providing context and a nuanced understanding of differences, but they also allow us to pull out commonalities across, in this instance communities, and this is what we desperately need in rural research. Because, if we rely on the much-repeated contention that there is only variation in rural, we miss a significant opportunity for collective learning and in my estimation, I think that’s what’s been happening, and that’s too detrimental.

Ron: The big experiment on health care transformation in the 2000’s, shifting from community health councils to large health authorities hasn’t worked very well from the perspective of rural communities. What have you found in your work with rural communities? How are opportunities for change being championed and challenges being mitigated with communities?

Jude: I know most of the local leaders I work with would definitely want community health councils back, without a doubt. We have to remember that regionalization was actually based on a promise of increased local responsiveness based on the recognition that, for example, conditions in Oliver in the South Okanagan is entirely different than those in Terrace, which is true. From the perspective of specialist care, for example, these benefits allow maintaining a reasonably sized call group and providing health human resource redundancies, but entirely disadvantages smaller general services. For instance, we have seen local services that are increasingly constricted with the assumption that it is better to consolidate one location. I actually agree that this might be true for some specialist and subspecialist services where you do want them located where you have a high procedural volume, but it is not true for primary care. What we have seen, and the starkest example of how this hasn’t worked, is in the closure of 20 maternity care services across rural BC where they have been centralized due to a confluence of policy issues and practical issues and health human resource issues that have been brought by centralization. The promise, the bold promise of regionalization, has not borne out for small rural communities. It might do well for larger size centres, but definitely has disadvantages for rural communities and by the way, when they first started to talk about this (I think it was a 2002 policy document), they warned that in the process of regionalization, we must be mindful and pay attention to the impacts on small rural communities, because they anticipated that they would be at risk of losing services in trade-offs for further centralizing care. So, there was an awareness of it, but that awareness actually didn’t lead to sustaining the services or stabilizing those services or putting resources and investments into the smaller communities. Another comment we hear a lot is that, although the intent of regionalization was increased responsiveness to local communities and local conditions, the historical mechanisms that you alluded to that were in place for health system communication are gone, i.e., we used to have hospital boards and health councils that were populated by local community members. It was for the community to articulate the issues of concern to the community and there was a direct channel from these boards to healthcare decision-makers. From an administrative perspective, it was argued that regionalization would make these hospital boards and councils unnecessary because you would have direct representation for your region. So, they were disbanded. But, nothing was instituted to replace them even at regional level and even at local level. We hear this a lot from rural residents who report a lot of frustration over the lack of mechanisms for engagement and people who have been around long enough, often hearkening back to the good old days of “hospital boards”. The hospital boards were disbanded because there was a heavy administrative and bureaucratic burden with them, and they were quite expensive. However, we can do better and there’s lots of potential for digitising or having virtual platforms to fulfill the same function, but we haven’t gone down that path. I’m waiting to see how that plays out with the primary care networks (PCNs). We haven’t really seen it consolidated in individual PCN’s, of course, and it’s not consolidated across the province as a provincial mandate which is what I firmly believe we have to have, and we don’t.

On that point, we now have a Parliamentary Secretary for Rural Health – Jennifer Rice as of January of this year. There’s a great role she could play in terms of promoting this.

Ron: Currently, you’re working closely with the BC Rural Health Network (BCRHN) in order to advance rural health. Could you please describe the role of the BCRHN and how the parliament secretary might fit in?

Jude: The BCRHN is a wonderful, truly grassroots organization that represents healthcare issues common to communities across rural BC from a community perspective. It all came from individual communities that banded together under the auspices of the BCHRN and they’re a very effective advocacy group. The quality that I really appreciate about the network is their community driven articulation of priorities. For example, they grapple with the concerns that they hear directly from the membership which is very different than responding to priorities established by the health authority or professional organizations (which happens in other mechanisms of engagement, for example, through the Patient Voices Network). The Patient Voices Network is also important, but it’s a different paradigm where the topic is already identified and articulated, and you get patient perspective. This turns 180 degrees and allows the communities to actually articulate what the issues are. So, I think that it’s essential and they also move from the idea of a patient partner paradigm which is rooted in the assumption of perspective, that is, individual patient partners bring their own experience to the table which is really valuable when it’s embedded in aggregate data. If you’re relying solely on perspectives, we are at risk of skewing our understanding of early issues based on the lens of particular individuals and we know the difficulty of including those that we don’t usually hear in these roles, namely, people from the marginalized communities or those representing marginalized communities. If we don’t have a very strategic and dedicated prioritized agenda for including a diversity of people in these roles, we are at risk and we do normatively value the status quo. That can be dissipated if we approach not the individual, but communities, which is what the BCRHN does. I actually think the role of the BCHRN is absolutely crucial. In my work in the past 20 years across rural BC, there’s never been an organization that actually fills the significant gap of conveying rural community voices to policy and decision-makers and advocating from an evidence-based perspective. In terms of our parliamentary secretary for rural health, I was delighted to hear the position announced. I was delighted to hear Jennifer Rice appointed to it and we’ll have to wait and see. I think she is fighting a bit of an uphill battle to represent marginalized views from rural communities when you know there’s a lot of focus historically and contemporarily on urban issues. Now that we’ve got this role, and I’m absolutely delighted, it’s kind of “let’s wait and see”. Hope for the best!

Ron: The BCRHN, in addition to advocacy, has also recently created three position papers to help bring about positive change for all rural residents. These include:

- Optimizing community participation in healthcare planning

- Travel subsidies for rural residents who need to travel for healthcare

- Relocation support for rural birthers

Could you briefly describe what each of these position papers is about and what they are hoping to accomplish?

Optimizing community participation in healthcare planning:

Jude: As BCHRN is a solutions-based organization, they try to come to the table with ways of addressing problems from the logic of community experience which many people believe is missing from a top-down approach. They have issued a series of priority issue papers. Their ground truth is coming from a living experience of people trying to access healthcare. So, I find them incredibly valuable. One of the papers is on “optimizing community participation in healthcare planning”. This position is based on the growing evidence on the value of community and regionally-based voices, and we hear that from our membership. What we’ve done, through the position paper, is advocated for a two-step process to work towards optimizing rural residents’ voices. The first step is based on best available international evidence and pan provincial community consultation that we did. We advocated for the BC government work with the BCRHN to create an implementation plan tailored to British Columbia’s geography and rural health services reality. The second step is that we recognize that we implore decision-makers to recognize that innovation is driven from within rural communities and occurs at a grassroots level across rural BC. So, local knowledge, local cultures, indigenous priority, and cultural sensitivities need to be the foundation of health planning and healthcare practice and this foundation will then create the models that will inform an overall BC relevant approach to residents’ voices in their health and health care planning. These were the issues we’ve tried to articulate in the first position paper.

Travel subsidies for rural residents who need to travel for healthcare:

Jude: The BC Rural Health Network was advocating on behalf of rural residents for increased government funding for those who require travels from their community to access healthcare. We were specifically advocating for full coverage for travel and accommodation expenses, for escort coverage, and that the coverage be available in advance of the required treatment or at the point of treatment to ensure treatment is sought. I have to say I’m always surprised by the number of people who live outside of rural (in larger urban centres) who aren’t aware that if you’re a rural resident living in Golden for example and you have a specialist deployment in Cranbrook, you are solely responsible for getting yourself to Cranbrook from Golden for that specialist appointment. Likewise, if you need procedural care either at a regional referral hospital or in a tertiary centre down in the lower mainland, you are responsible for getting yourself to that care unless your status is indigenous. There is currently no extra funding to help with that. That is a huge expense for a lot of people, and it actually is care limiting in the sense that people will opt to not go for care until it’s a dire emergency which, of course, creates more health system utilization. If we would have dealt with it upstream, it wouldn’t be such a problem later on. So, that lack of facilitation of getting to and from your small rural community disadvantages the vulnerable populations the most (The ones who don’t have available income even if it’s a refundable trip). But, to pay upfront? I’ve talked to many people who say they can’t afford the bus fare or the hotel to go to the appointment, and their appointment is at 8:30 in the morning and the communities are three hours away. All of these issues that we don’t really think about from an urban perspective become increasingly important as we are trying to deal with what I call the tyranny of our rural geography. We have communities that are great distances away from larger centres. It’s difficult. We’re really advocating for full coverage. Interestingly and almost kind of ironically, I was very interested in the announcement by the BC Minister of Health with regards to subsidized funding for people who will now be traveling to Bellingham to access health services for cancer treatment. Because, rightly so, we need to get people to treatment as soon as we possibly can. I think it’s totally appropriate that there are travel accommodation and escort even paid for in advance. I think that’s entirely appropriate. However, what’s not appropriate is that the people who need to make the same kind of travel within BC do not have any of those supports. If you live in Smithers and have to go to the Lower Mainland for cancer care, it’s on you and that is exceedingly expensive. I am really hoping that the announcement of subsidized funding to go out of country (which we can debate the merits or the lack of merits of this later on) that those same supports are available to people who are staying in British Columbia. It’s really a great example of inequity.

Relocation support for rural birthers:

Relocation support for rural birthers focuses our first position paper on travel support across rural BC. We know that the best care for birthers is care as close to home as possible in a safe protected environment, but there are instances in the rural population that definitely cannot safely support a maternity service. There are not enough births per year, for example, due to low volume of deliveries. There has also been increasing instances of rural maternity services like Salt Spring going on diversion due to staffing and transport issues. In these cases, birthing families are required to leave their communities for the intended place of delivery before the onset of labour. This may be two to three weeks prior to the due date and follow-up care is required after birth. They need to spend maybe a month in a referral community or longer if they run into complications. So, although travel and accommodation are covered for status First Nations families, expenses are not covered for others, leading to substantial out of pocket costs. This creates an undue burden on rural families and effectively limits access to care. We’ve also seen the rise in unassisted home births. People do not do unassisted home births for political reasons or philosophical reasons (like, say, in the heart of Vancouver), but there are people who do because they feel they don’t have other choices. So, they need to stay and birth in their community. We are advocating for the Ministry of Health to partner with communities to determine the appropriate system supports needed so families can access intrapartum care. We specifically advocate for financial and social support and accommodation for travel in instances when care isn’t available locally; and this should include full coverage for travel, accommodation and escort coverage, and that coverage being available in advance of relocation. When we think about Canada, we don’t think about the cost of healthcare. However, we think about that in the United States a lot: “How much does it cost to have a baby”? Well, I’ve got to tell you that rural families weigh the costs of having a baby when they have to leave their community and, for some, it’s too much.

Ron: I know you’ve explored ArcGIS for real-time input. Is that something that you could see being used through community participation so that there’s a lot more ‘real-timeness’ to the planning as opposed to what we have accomplished in the past?

Jude: Absolutely! We have to realize that research timelines are not decision-making timelines and conversely decision-making timelines are not research timelines. I remember one of the cathartic moments for me was when a colleague in the Ministry called me up and said, “we really want to understand the implications of community paramedics”. “Could you take a look and do some data gathering on this for small rural communities?” and I went saying “ok, I’ll apply for a grant. The grant deadline is in four months, and it’s adjudicated in a year. It will take me about a year to get the grant and I can get you something back in three years”. Well, that just doesn’t work. We absolutely need more rapid access to rigorous data that does not mean cutting corners and taking shortcuts. It just means focused rapid access to answering some of these questions. So, that is one part. The second part is that there’s a fair amount of cynicism in rural communities about return of data. When they participate, whether a resident or a community leader or a healthcare provider, the issue is that how they see it returned in the form of policy change. Of course, as health services researchers, we’re not responsible for the policy change, we are responsible for working with the policy-makers to understand and implement the evidence, but we can never ultimately guarantee there’s going to be policy change. So, the slowness of this process has really created a lot of cynicism amongst rural communities. I believe we need a lot more transparency. When people are putting data into a project or answering a question, they need at the very minimum to be able to see first of all what other people are saying in a timely way and understand what the accountabilities to using the data are. It’s not that every decision will be based on what the community says. But, we do want some assurances that what the community says is weighed alongside all the other evidence cycles into health planning. Both of those issues are really important and can be facilitated by, as you say, for example, a virtual platform where we can do things much quicker, much more efficiently, and with greater transparency and, yes, we are looking at using ArcGIS Survey123 to do that.

Ron: You’ve accomplished and published a lot of research around rural health and are keenly aware of the challenges of getting findings into policy and practice. Who needs to be made aware of rural health research and held accountable for implementation? Could you please discuss these challenges and how they might be best mitigated?

Jude: Accountability has to happen at a local municipal level. It has to happen at a regional level with the health authority who’s delivering the services, and it has to happen at a provincial level for the policy in terms of the policy creation to be rurally responsible to take in the data and evidence from communities. However, other partners need to be accountable as well (e.g., the professional associations). The challenge is “how do we hold them accountable”? To do that, we have to understand and address the gap between, for example, the rural community voice, the community-oriented outputs of conversation and advocacy into policy and decision-making, and its uptake into planning at provincial and regional levels. I think some of the issues we need to be thinking of is our starting with the big question which is “what culture change needs to occur to increase the receptivity of the outputs of community-oriented voice into policy and decision- making”? Because culture is a huge part of it. Are we just nominally valuing the notion of evidence-based policy, or do we actually want to dig into the evidence base and have it inform our policy? By the way, when I talk about evidence, I have an expansive definition of evidence. Of course, it refers to rigorous, peer-reviewed, published works, but my definition of evidence also includes the individual lived experience, the collective of the individual experience, consolidated in communities as well as policy directives that are kind of inferring a direction one way or another. Taken together, that is all part of evidence and that requires culture change at all levels to be embracing as opposed to be resentful or afraid of evidence. The other thing that we have to be thinking about is “what’s the role of community voice in policy formation at a regional level like a regional health authority level and provincial level from the perspective of those creating policy”? Do they value the consolidated community voice for influencing how their policy is going to roll out? And that leads to a very tricky question which is “how community input weighs alongside other policy influences such as the available resources at hand, the political values, the electoral cycle, cultural beliefs and all of the other things that go into making policy”? How much weight do we give to the role of community voice, and I don’t think we’ve really worked that out and, of course, there’s not going to be a standard answer across the board. Those questions are not in common parlance. The other thing we need to be thinking about to bridge this gap is “what level of priority are we giving to diversity of voices and how is diversity included and facilitated”, like hearing the voices that are not usually heard in healthcare planning? It takes a lot of extra effort in part because of the cynicism involved with these subgroups where they have not had the experience of being listened to. They don’t believe they will be listened to. We need to ask them how they want to engage and then take that engagement back to the policy and decision-making. I guess the last thing I would think about is “what are the gaps in resources that are needed to actualize the inclusion of community level evidence or community voice in healthcare transformation”? Because if we are not resourcing the people who are making the decisions appropriately, it’s going to be very difficult. That’s not more of how do we do it. It is how do we set the infrastructure up to allow this to be successful, but I’m just going back to the very first thing I said. Because I believe the absolute most important thing is “culture change”.

Ron: You mentioned the right direction for the research community and that would include, I presume, the funding institutions because you mentioned earlier there’s a big lag time between applying and actually getting funding and, then, the results in terms of years. Are you aware of any institutions that actually have sped up these cycles so that we can have more ‘real-time’ research and findings put into practice?

Jude: It’s not like they can’t do it. We saw an incredibly rapid turn-around when we needed data about COVID-19 in the pandemic. CIHR had about a three to four months turn-around from an application to release of funds since we needed the data expediently. So, it’s not like we can’t do it. It’s that we don’t. At a local level, I want to shout out the amazing Social Planning and Research Council (SPARC BC). They did an incredible turn-around from an application to us receiving funds. This past cycle was about three months, or maybe even less, to start looking at issues of quite urgent importance around getting evidence into policy and planning, and they deemed that as a provincial priority. It was a very quick turn-around. It’s not like we can’t. It’s more about that we don’t and maybe that’s because we don’t recognize the value of rapid access to data and rapid return on that access to data.

Ron: In conclusion, is there anything else you would like to highlight around rural health issues?

Jude: I’m just going to look back to what you said: “Are we moving in the right direction?” Of course, more can be done. There are system-level initiatives right now that seem to be moving in the right direction, but I would frame this more around something I’m interested in which is “whether or not the research community is moving in the right direction in taking up opportunities to understand the innovation that’s happening in rural settings”. For example, whether or not really inspired innovative models of care such as “family physicians with enhanced surgical skills offering procedural care in small volume communities” (which I think is absolutely brilliant) might be of value in larger centres. The advantage of rural research for me has been that there’s a very clear population denominator. So, for example if you’re looking at models of care in Salt Spring Island, you pretty much know where your population is. Because we are on an island. You’re going to be receiving care from local communities. Some people go off the island, but most people receive care from local communities. You can really accurately measure the health outcomes and the impact on local population. That’s actually a huge advantage, but you know whatever we do it’s really crucial that we engage with rural communities to make sure that we’re applying a local lens to any analysis. All I would say is that there’s a great opportunity for us to take up the collaborative community-engaged rural research in a meaningful way.

Interview Series (Dr. Wei Zhang)

Interview with Dr. Wei Zhang: A Tribute to her Contributions to SPPH

1) Would you please elaborate on your role and contributions as director of the Master of Health Administration (MHA) program at SPPH?

The same year I started to teach MHA students, I was appointed as the associate program director. I engaged in admission processes as part of the admission committee. Moreover, I played a fundamental role in guiding the students through their capstone projects. In fact, MHA students need to do a capstone project and write a report instead of a thesis. To ensure that students complete the capstone project on time for graduation, I introduce the capstone project to them in a workshop before the summer in the first year of their studies so that they have time to think about their project topics. In the second year, I set up office hours to meet with them to give them feedback on the scope and feasibility of the topics they came up with on a case-by-case basis, and review and approve their proposals. Then, they start conducting their projects with their supervisors. If they come across any problems while conducting the projects, they will also approach me. Finally, after submission of the grades recommended by the supervisors, I ultimately review their final reports and give the students their final grades.

2) Would you please briefly discuss the graduate-level courses you have taught at SPPH?

I mainly taught two courses at SPPH and both were in the area of “economic evaluation”. I’ve been co-teaching SPPH 541 with Dr. Aslam Anis since 2014 and teaching the course myself since 2022. This course is offered to SPPH graduate students except for students in the MHA program. Then, from 2019, I started to teach SPHA 531 to MHA students. In this program, we are trying to educate future leaders in the healthcare system. So, the course is tailored more to the needs of possible future leaders in the field.

3) What is your approach to teaching “health economics” to graduate students? How do you manage to meet different learning objectives of students with different backgrounds?

This is really an important question since many students find economic evaluation challenging. I tried to use an evidence-based approach in designing economic evaluation courses. I’ve always tried to use many real-life examples to help students link the theory to actual problems. I usually start with basic concepts and then real-life examples follow. I utilize various quizzes and group discussions with the goal of engaging all the students and helping them to meet the course objectives.

As for the MHA course, the students’ needs are different. MHA students are less likely to do the economic evaluations themselves in the future. They need to understand the concepts and be able to appraise the economic evaluations. They are in fact future decision-makers compared to students in other programs who want to take economic evaluation as their future research area. Therefore, there are some differences in designing these two courses to meet different objectives of the students. As for MHA students, I’ve engaged decision makers in BC Ministry of Health to talk about the ways they use cost effectiveness evidence to inform their decision making regarding which drugs and health technologies to fund.

4) Would you elaborate on your role in developing curriculum for different courses/programs at SPPH?

As for SPPH 541, I did some changes in the curriculum. For instance, I simulated randomized clinical trials’ data to help students learn and practice cost-effectiveness analysis based on clinical trials’ data. As for SPHA 531, their course was offered through the weekend, i.e., one long day of teaching. So, I designed lots of “in class activities” besides lecturing. A lot of group discussion sessions were designed to give them a break from all the lectures and provide them with the opportunity to share ideas in the group. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to use blended approach. So, I prepared lots of asynchronized material to make full use of students’ time for gaining the required skills and knowledge. And during the synchronized learning, we mostly used the time for problem solving and clarifications and group activities.

5) Would you please talk about your Continuing Education (CE) activities?

Apart from teaching students, I would like to share my knowledge and expertise in terms of “work productivity loss” measurement and valuation with other researchers in the field. “Work productivity loss” is seen as “Indirect Cost”. If we look from the societal perspective, “work productivity loss” is really an important cost component in economic evaluation. I provided one workshop for clinician investigators to help them understand how to incorporate economic evaluation in their clinical research. Moreover, I organized a training workshop at the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) symposium for researchers, policy makers, and trainees.

6) Could you briefly discuss your research activities, your role and contributions in providing evidence-based research on “drug and health technology funding decision process”? For instance, you have conducted great research on “pharmaceutical pricing policies” in Canada. You have indeed conducted the first studies on the impact of price-cap regulations on market entry and exit.

I work closely with clinical investigators and most of the topics for cost-effectiveness studies come from the clinical investigators themselves. They usually approach me to conduct the studies since evidence from cost-effectiveness studies is commonly required by decision makers in order to decide on funding.

As for “pharmaceutical pricing policies”, I started to work on generic drug pricing policies. Use of generic drugs reduces expenditures while increasing access to medications. We evaluated price cap regulations (generic drugs priced maximally at a certain percentage of the associated branded drugs), the recent tiered pricing framework (not a fixed price cap) and the impact on generic drug market entry and exit in Canada.

The other topic I worked on was “drug shortages in Canada”. Since 2017, manufacturers must report drug shortages and drug discontinuations to Health Canada. We used that data to identify factors associated with drug shortages in Canada. One of the important factors was found to be having a single supplier for a drug.

We currently have a CIHR-funded grant to look at patented medicine pricing regulation. In Canada, patented drugs are regulated by Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). In the past years, they were trying to amend their existing price regulation. In fact, Canada ranks 4th (after US, Switzerland, and Germany) with regards to price of patented drugs in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. So, patented drugs are very expensive in Canada. PMPRB has proposed some amendments to address this issue. It is actually a very long process. We as independent researchers are trying to evaluate the potential impact of the proposed regulation. For instance, we are looking at whether manufacturers are willing to launch their patented medicines in Canada and also the impact of the proposed regulation on the price of the patented medicines. We also engaged different stakeholders from BC Ministry of Health, Public Health Agency of Canada, CADTH and Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. We will share our findings with the public and stakeholders.

7) How do you connect your research findings with healthcare policy planning?

We all know that it is important to have research questions that have implications for healthcare policy planning and are relevant to current needs of stakeholders. We have connections with BC Ministry of Health and we communicate with them to be aware of their concerns. We also engage them in our studies especially for results interpretation and knowledge translation. We actually have a great network of researchers and faculty members at SPPH who have great connection with policy-makers and stakeholders; paving the way for connecting our research findings with healthcare policy planning.

8) In general, what is the role of empirical research (health economics and pharmacoeconomics in particular) in generating evidence for decision makers in the healthcare system?

After a drug is approved by Health Canada, CADTH assesses the drug both from clinical perspective (clinical effectiveness) and economic perspective (cost effectiveness). Health economics and pharmacoeconomic studies are needed to inform CADTH’s assessments and recommendations that are provided to federal, provincial and territorial governments for their reimbursement decisions. Finally, these governmental bodies, for example, BC Ministry of Health will decide on the drug coverage under BC PharmaCare plans. Similarly, for health technologies, they look at cost-effectiveness evidence when making funding decisions.

Archived Interview Series (Glory Apantaku)

Interview with Glory Apantaku

1. How did you manage to enter the rural community in a trusted way to engage community’s voice and wisdom to conduct your research?

From the very start of the project my team members, Magda Aguiar, Mark Harrison, and Theresa Healy ensured that we thoroughly engage with the rural community. Theresa Healy, who is based in Prince George and has worked extensively in community engagement with rural and remote communities was a very helpful guide and made sure that we were connected to variety of people. There were also some components of the project that were informed by the ministry of health (MoH). Magda had connections within MoH that helped us to get connected to people from the health authority. People from other parts of the northern BC were in our group from the start as well. We had Lara Frederick on the team. She works with Northern Health and is based in Dawson Creek. She helped us with participant recruitment. We also had a community partner based in Valemount. We had a lot of snowball sampling, and we were connected to people who had already extensive community network and they supported the recruitment process. As we were in the middle of the pandemic, having those community partners from the beginning was really everything.

2. On that point, was the work done mostly virtually or face to face?

The work was done virtually as it was in the midst of the pandemic.

3. How did the virtual connection (as opposed to face-to-face connection) affect the level of trust? Did the medium affect the level of trust in any way?

I would say it did not affect the level of trust because of the snowball sampling. Mostly people who joined our focus group sessions knew somebody who knew somebody else. So, they were all brought to the session by a trusted party, and it was almost immediate comfort. As it was pandemic and people had not seen each other for a while, they were happy to have the opportunity to spend time together and share stories and talk and learn from each other. We were also worried about the issue that virtual connection may be weird, and people may not be comfortable about it. However, they were pretty fine with it, and it was great and actually worked out for us.

4. Would you summarize your findings and tell us take-home notes of your research?

We had three main methods of data collection: focus groups, interviews, and photo voice. So, we had multiple streams of data and had a variety of results to disseminate. We had strength-based results that were focused on the fact that people are excited about their community. They love where they live, and they do not want to move to an urban area despite all the challenges. They were very proud of their community. That was like a big takeaway for us. The decision makers and the leaders we spoke to talked about the need for minimum standards of care and the fact that if we can agree about the minimum standards of care, we all work together towards achieving that minimum standard, instead of having so much uncertainty around what we can do and what we cannot do and having those conversations again and again. There was also a big chunk of conversation on the fact that communities want to be more involved in the process of welcoming physicians and health care workers and being engaged in the process of hiring them. They didn’t want the decision-making to be so high level as being based in Prince George or Victoria. They wanted to be more connected to the decision-making process. They wanted more devolution of the power so that smaller communities have a greater voice in decision making by using tools like “community health boards”, something that connects the community to the health system more directly. There was also conversation around patient navigation and the fact that people need support to be able to know what services are available. They weren’t all focused on saying “we need more services” but rather said that “we don’t even know how to access the services that are already available”. So, there were multiple domains of results. There is also a broader sense of the fact that people understand that resources are scarce. They know that because they live so far away, they are not able to have everything they want and that’s not what they are asking for. They want to make sure that anybody needing care in McBride for instance can be supported to travel to Prince George or Vancouver or wherever they need to travel to. Nobody expects to have a hospital in every community. That’s unrealistic and they understand that. They just want to make sure that people are supported to access services and that was a big part of the conversation.

5. You talked about looking at “community health boards” again. As you probably know community health boards were tried 20+ years ago during the early stages of the health care reform. This is really like revisiting history that the community really wants to have their councils back for that local voice. I guess in the current structure it is getting lost. What was your intake on that?

That is exactly what they were telling me. That they had those community health boards, and they were able to go to those health boards and have those conversations. According to them, the heath system is so far away and with those community health boards they didn’t have to try for weeks or months to contact one CEO of a large Health Authority that serves a large region. They said that they rarely hear from them because they are often very busy with dealing with other things and the connection is limited. People were telling me a lot about that history that they saw a value in having those community health boards.

6. With respect to this experience and findings of your research how do you think we can tackle this problem of going back and forth? To put another way, 20+ years ago, it was realized that it’s a good idea to have those community health boards but they got lost in the current health structure. Do you have any idea on how to tackle this problem?

I’m going to humbly say “I don’t know”. What I heard people saying was very much about having a lot more voice and involvement in decision making. The fact that people are actually engaged in decision making sometimes enriches the quality of the decision. It doesn’t mean that the decision will always be great and always favor everybody. They don’t expect that there will be solutions all the time. They believe that if they are involved in the decision-making, the decisions would be better for them. They believe that they may not get more doctors immediately but in the long term, maybe the one doctor that they get visits more often. They don’t necessarily expect that the doctor stays, but maybe the one doctor they get comes once in three months or once in six months instead of never coming and they always having to go to Vancouver for their medical visits. They just want to achieve something more equitable.

7. How are you planning to put your research findings into action?

I sent you the link to our photo book (https://www.pluralbc.org/book) and a high-level summary of our results like a lay summary. We sent the book to various places across BC. We sent that to people at Northern Health and MoH. We shared that with health economists, researchers, mayors, and councillors. We are going to write a research paper, but we felt that a mayor may not engage with a research paper which is fair enough. So, we tried to make sure we have multiple ways of sharing the results. We had a photo exhibition where we showed the results of our photo voice activity and then, we had the mayor coming in and seeing the results. We also had researchers coming in and seeing the results. So, we had multiple ways for people to engage with the results of the study. One way to put our results in action was to make sure that all people having any kind of power would have access to the results and be able to have the hard copies and read them. We sent the books to libraries across Northern BC. We really distributed those photo books widely to make sure that a lot of people be able to see the results, engage with it and just know that this research is happening and have a sense of what people are talking about when they are talking about health services in those communities.

8. Have you made any connections with BC Rural Health Network at all?

Yes, we did. One of our team members, Magda connected with Dr. Jude Kornelsen at the beginning of this project. We used some of the results from one of their projects in one of our focus group activities. So, when we were asking people questions about preferences about access to health, we were using results from one of their research activities. We used a lot of that work in informing our questions, designing our questions, and our focus group activities.

9. How was the uptake of your research findings by policymakers? Did you receive any feedbacks in this regard?

It’s really hard to measure uptake by policymakers. I think my proudest moment was when the CEO of Northern Health emailed me and asked about the book she heard of, she wanted to buy a copy. There were also people from the MoH who sent us messages and said that “this is great”.

10. “Relational Competence” is a very important term in collective creation of knowledge. Which elements of “relational competence” should be considered to make sure that a trusting relationship will be developed, nurtured, and maintained?

We prioritized that relational engagement with people. After one session of photo voice, we developed a kind of fluid, friendly, and conversational environment. Our participants asked us about the output of the study and they shared their ideas on what they wanted the output to be. We couldn’t say that the only output would be a research paper. So, the photo book that we designed was actually a response to the ideas our participants shared for an output that could potentially engage people. We cared about what people said. We took it to heart seriously and we went and wrote a new grant application on the knowledge translation. We were lucky to get the additional grant funding we applied for. It helped us fund additional knowledge translation activities. We learned that people don’t care as much about the conference presentation or research article. They want us to bring back the results in a way that they can engage with. That sense of reciprocity and engagement with people’s feedback is really important. Taking what people said and acting like it matters. For this project, we had to get an extension on our research project timeline at least once. We can’t be rigid as a participant in a relationship. We have to be willing to move and align with the flow of what we are learning from our participants. It can be pretty hard but it’s important.

Note: Your results also emphasize the importance of qualitative methodologies. The importance of visual methods within the qualitative methodology. Quantitative side and statistics have taken too much importance. We need to shift the thinking especially in the KT world in a way that people can relate to the data in a better way than they did in the past. Otherwise, it would be a research project that no one is going to read about or a presentation that is boring and no one is going to engage with. This is much in keeping with expectations in real life and especially for laypeople. It’s a huge message that you can move forward here in terms of findings and also the fact that how the funding mechanism needs to catch up to allow us much more flexibility in terms of timing, money and order of things that are happening.

11. The reciprocity and “Cultural Mutual Dependence” especially in Northern and remote settings are explicit. What can the urban culture learn from the rural?

The theme that urban can learn from the rural is consistent acknowledgement of mutual dependence. In urban areas, we sometimes act like that mutual dependence is not the case. Human beings know in a sense that there is a level of mutual dependence but in rural areas, it is more explicitly acknowledged and there’s also more room to allow mutual dependence to occur. In rural areas, there are spaces that are specifically designed to respect mutual dependence between people and there is more explicit knowledge sharing. There is more involvement in decision making. People are connected. People were telling us that there were people in the community who were “patient navigators”. They were not paid to do all the things they did. Patient navigators were merely people who knew all these things and helped people figure out where they needed to go to receive the required services. These are necessary even in urban areas where there are much easier ways to access services. Sometimes people just don’t understand the intricacies of the system. In urban areas, we fail to understand that mutual dependence is important probably because we assume that people know. But in rural areas this assumption is not the case.

Archived Interview Series (Dr. Jason Sutherland)

Interview with Dr. Jason Sutherland

Dr. Jason Sutherland

1. What is the overall structure and function of Centre for Health Services and Policy Research (CHSPR)?

The Centre for Health Services and Policy Research (CHSPR) is an independent research centre within the School of Population and Public Health (SPPH). Currently, there are 6 core faculty members in the centre. I am the interim director of the CHSPR. The other members of the centre include Drs. Michael Law, Kim McGrail, Sabrina Wong, Rubee Dev and Mahsa Jessri. In addition, the centre has a number of associate faculty members. We are currently in the midst of planning to host our 35th annual health policy conference.

The CHSPR is located on the second floor of SPPH. We have a physically secure space, wherein physical access to the centre is restricted because of proximity of potentially identifiable data. The CHSPR is co-located with PopDataBC (https://www.popdata.bc.ca/).

The centre has a couple of staff and a significant number of graduate students as well. So, the physical space of the CHSPR includes faculty, staff, and graduate students working towards obtaining their Master’s in health sciences, Master of Science and also PhDs. So, every day there is a handful of people working there.

Each of faculty members of CHSPR has different lines of scholarship. Dr. McGrail does a lot of research on topics pertaining to data governance, data linkage, ethics of data, and using population health datasets. Dr. Law works on pharmaceutical pricing policies and access to therapies. Dr. Wong who is a faculty in the School of Nursing, conducts research focused on primary care and primary care delivery in delivery networks. Dr. Dev in the Faculty of Nursing conducts research on factors associated with primary care quality. Dr. Jessri is in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems and conducts research on associations between diet patterns and chronic diseases.

I conduct research in two themes, or areas. The first theme is centred around health services and policy research. In this research, large data sets are used to drive policy-relevant analyses. My second theme of research is focused on surgical outcomes. Currently, I lead a program of research measuring patients’ outcomes from elective surgeries in six hospitals in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority.

In the CHSPR, I also lead commissioned projects or commissioned research on behalf of provincial or federal governments or non-profits on specific topics or issues. For example, I just completed some research on behalf of Health Canada examining issues associated with readiness to proceed with health care funding reform.

The second theme of research is focused around measuring health outcomes attributable to elective surgeries. My research team identifies patients scheduled for elective surgeries for 8 surgical specialties in the six Vancouver Coastal Health Authority hospitals. We contact them and have patients complete a number of surveys, asking about their health, well being, functional limitations, and symptoms of their conditions. We also collect the same data postoperatively to understand changes in their health attributable to their surgery. The patient-reported information is linked with the large population-based administrative data sets to understand health care costs associated with their treatments or to shed light on how much healthcare they consume that is not surgical during their waiting time or to identify factors associated with re-admissions.

2. With respect to your second theme of work, what sort of questionnaires do you usually use to measure patients’ reported outcomes?

We have a constellation approach to measuring patients’ outcomes. Irrespective of the type of surgery that the patients are scheduled to have, we have a core set of measures which include their health status, depression, anxiety, pain, and also their decision confidence in how they evaluate communication with their surgeon. Then, depending on what they are scheduled for we also ask the patients to complete another questionnaire pertaining to the symptoms or functional limitations of the surgery. So, we have over 60 unique questionnaires that patients are asked to complete depending on what patients are having surgery for.

3. What are some examples of current research projects conducted at CHSPR?

One of the current projects that we have underway with one of my graduate students is measuring access to surgical care among immigrant communities in British Columbia. So, we’re trying to understand whether or not new immigrants to British Columbia access healthcare differently and whether or not that impact their wait times for surgery. This research is linking the immigration data with the health care utilization data to be able to understand how long the new immigrants wait for their surgeries versus non-immigrant British Columbians and compare whether or not they wait more or less. We are also looking at the patterns of health utilization before patients get to the surgeon and whether or not they go to the emergency department first to seek their health care. So, what we’re trying to do is we shed some light on health seeking behaviors of immigrants compared to non-immigrants.

4. How can students get up to dated with regards to news and events held by the CHSPR?

Every two months, CHSPR hosts a research seminar that’s open to the public. For the seminars, we have external speakers who come in and present their research and have a question-and-answer session as well. Moreover, every second month, we have a series where students present research papers on methods and topics they found compelling. So, those student journal club presentations are scheduled to occur every second month.

5. How do you think the CHSPR paves the way for a sustainable publicly funded health care system in the long term?

From my perspective, the research output and policy analyses generated by CHSPR, its graduate students, staff and faculty are used as inputs for the creation of evidence-informed policies. Those research outputs that intersect health services and policy research helps inform evidence-based decisions regarding access to care, quality of care, and issues relevant to British Columbians accessing healthcare. The way CHSPR is different from the other health services or policy research conducted by other faculty and schools is that we try to integrate the health services research with the policy analyses and use our links with senior decision makers within the healthcare system to try to give them the evidence so that they can make informed decisions.

6. With respect to funding, do you receive funding from any external sources?

Individual faculty members are encouraged to apply for peer reviewed funding. Otherwise, the big activity that CSHPR leads is our annual health policy conference. Our 35th Health Policy conference is coming up in March and we expect over 250 health care policy makers, academics, graduate students, clinicians, and patients to attend. This year’s theme is “Value and Healthcare”.

7. Is there any other specific topic that you would like to mention?

I think CHSPR faculty, staff and graduate students fit nicely within SPPH and other faculties’ programs of research. Because the research and policy analysis are complementary, I feel there is no competition between the researchers but rather they add value to each other. I think that is one of the significant contributions of the CHSPR.

CHSPR is always looking for new collaborators. So, we engage with senior policy makers and senior clinicians within the health system. For example, I work with the heads of surgery across Vancouver Coastal Health Authority to study issues associated with equity of access, social determinants of health and those sorts of policy-relevant questions pertaining to surgery. The other CHSPR faculty conduct similar applied knowledge translation with decision makers in their own programs of research.

Archived Interview Series (Dr. Dean Regier)

What was the rational for establishment of the academy of translational medicine?

Dr. Dean Regier

The academy of translational medicine (ATM) is a combination of 5 years of engagement with translational medicine researchers within the faculty of medicine that collectively identified several important key challenges in terms of translating new therapies and new health products to patients. Those challenges included:

-) Underdeveloped funding.

-) Insufficient collaboration and by that we mean “Interdisciplinary Collaboration”. So, people from multiple disciplines come together to create an approach moving forward. To translate new health products into medicine.

-) Limited knowledge at UBC in terms of understanding the pathway to getting a new product to the patients. By the pathway we mean starting from the manufacturing to evidence generation pathway, to regulatory pathway, and to reimbursement pathway. They are all indeed linked. SPPH can conceptually fill that role. But the link between different departments within the faculty of medicine is not strong. To that end, there is a limited understanding of regulatory and reimbursement roadblocks.

-) Challenge with respect to our technologies, processes and facilities with respect to data capabilities to what we call it “innovation ecosystem”.

What is the vision?

The vision is big. The idea is “How to reduce the timeline for translational medicine by at least 50% over a 10-year period”. It gets something like 12 to 17 years to get the patients and reducing that to half would have a great impact.

In terms of the focus areas, the focus areas are around integrating UBC departments and schools, research centers and institutes, Health Authorities and industry to all come together and support data platforms, research capabilities, educational programs and content experts.

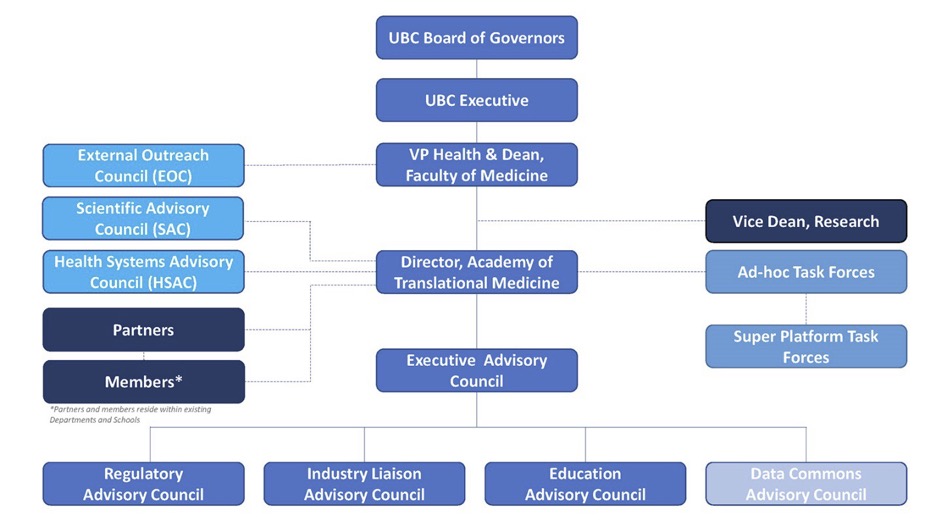

What are the structure and functions of ATM?

We’re developing 4 councils (as it stands now): 1) Regulatory affairs council. 2) Industry liaison Council. 3) Educational council. 4) Data commons council.

Those councils are governed by an executive council which rolls up into the ATM.

What other schools do you work with apart from school of medicine?

We work both within school of medicine and across UBC. We work with business school (Sauder) and School of biomedical engineering (SBME).

It’s a neural network where we can be a hub for all these really important initiatives and try to bring/ stich people together. We try to come up with a way by which investigators and programs interested in interdisciplinary work can come together and create something special against that backdrop of regulatory affairs, regulatory science, data commons, industry partnership, etc.

What are examples of current research projects conducted?

We don’t have any research projects per se: we’re only 2 years old! We’ve had early success with funding and creating educational platforms, a regulatory science micro credential funded by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training. We received that last March. That micro-certificate is an overview of key components of regulatory affairs and regulatory science and health economics.

We also have a regulatory affairs council that helps us build out the future of ATM in terms of helping the BC ecosystem navigate regulatory roadblocks and for helping us establish the future of regulatory science education at the faculty of medicine.

For future research collaboration, the ATM wants to enable science and enable scientists to come together to co-create interdisciplinary research that is cutting edge. We aim to focus on what kind of physical space, what kind of environment can be put together that really allows investigators across UBC and faculty of medicine come together.

We have been talking to a whole bunch of research programs (e.g. a group called “mend the Gap”). A recently-funded project which mends spinal cord injury. What we’re doing is that we’re talking to them about with whom we can connect them. People they think can help them with regulatory aspects of both a drug and a medical device, both wrapped up in a medical treatment which is a novel pathway in terms of regulatory approval process.

To your point on “micro-certificate course”, are there any other upcoming courses?

We are talking to SBME about creating new courses. We are thinking about having something more in depth around regulatory affairs and regulatory science related to evidence generation. By that we mean more in depth conversations around adaptive RCT designs and Patients engagement. We know regulations around conducting a good RCT that is important for Health Canada but “How do we innovate on the types of evidence that we generate in a way that allows us to move forward innovations in a safe, efficacious, sustainable manner but also in a timely manner. Do we create another arm of the micro credential? Or do we start to create graduate programs related to evidence generation for innovative technology and other regulatory affairs and regulatory science requirements associated with them?

Can students outside UBC participate as well?

Yes. It is a partnership between the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training and Faculty of Medicine. So, we make sure to offer scholarships. Especially scholarships to people who need them. These courses are expensive. We tried to think about diversity in terms of who deliver the lectures and make sure there was depth in variety of perspectives. We also thought about “how we get more diverse students per learner population be aware of the course”.

How can students get up to date with regards to the news and events held by ATM?

We have a Newsletter. The faculty of medicine amplified it quite a bit. For the micro-certificate we had a whole bunch of different partners, industry partners. We had Pan-Canadian regulatory professional associations that we advertised bit!

We had 29 people in the first course. We put it together in 3 months. And then 20 people in the 2nd course. 49 altogether!

Does the academy give students insights on how to commercialize patents?

In the second course, we talked about Intellectual Property and its role in society. We did have an entrepreneurship course that talked about commercialization, partnered with Sauder School of Business.

How do you think the academy paves the way for a sustainable publicly-funded health care system in the long term?

From an economist perspective, what I’m really interested in is the ATM furthering a sustainable public healthcare system in line with public value. Typically, in conversations around discovery and innovation, it’s really upstream like “here’s the genomic test that can inform treatment”. Or “here’s the new treatment that may or may not improve the health of patients”. It’s really what I call upstream thinking. What the ATM is doing is conceptualizing innovation across the entire life cycle of the health product or technology. We take a broad approach, understanding that we need safe, effective, and cost effective drugs and technologies to improve patient and population health. As an economist, it’s near and dear to my heart that the health products we fund are in line with the values and priorities of all aspects of the public. We stich together these conversations of sustainable, cost-effective healthcare and we have these conversations with people who are making these discoveries. Then, we can plan all relevant scientific query at the beginning, knowing what we want to get out of healthcare in the end. Having these conversations with people upstream, in terms of this is what you need to understand, what is valuable to the healthcare system, why population health is important. These conversations aren’t always happening. This is part of what makes the ATM innovative. Usually, you have statisticians, epidemiologist, economists not really talking to the scientists who are making these discoveries. We want to stop being insular and say let’s work together at the beginning to help navigate that entire pathway.

Does ATM have a venue (logistics)?

We are working towards getting a physical location. We are located across UBC and affiliated sites from a physical perspective. We currently have virtual venues.

Is there any other specific topic you want to mention to be addressed in the newsletter?

What we at the ATM are interested in is accelerating innovation to patients. But those innovations need to be safe, efficacious, and sustainable. In my view, the way to achieve this goal is through marrying regulatory science – broadly the work advancing science around the tools of evidence generation (e.g., real world evidence, adaptive clinical trial design, patient engagement) with priority topics like priority pathogens, personalized medicine, advanced therapeutics, artificial intelligence, etc. So, we see regulatory science as a real way to help sustainable innovations move quicker to patients. Again, part of the conversation is that we need to partner with government and industry in order to move some of those conversations forward.